Search

When Your Spouse Is Ill, What Does the ADA Really Protect?

A new Eleventh Circuit decision shows just how limited associational disability discrimination claims can be.

TL;DR: A deputy warden sued after being passed over for promotion, alleging her husband’s serious illness led to discrimination. The Eleventh Circuit rejected her ADA claim, emphasizing that associational disability claims require a strong causal link—not just a stray comment or a caregiving assumption.

👉 Read the full decision here.

A missed promotion and a murky comment: Was it discrimination?

A former deputy warden alleged she was denied a promotion because of her husband’s serious illness. She pointed to a supervisor’s vague remark about needing to “lay off of” her due to her husband’s illness as evidence that her caregiving obligations were viewed as a liability.

The employer countered with interview scores, qualifications, and a structured evaluation process showing the selected candidate was objectively more qualified.

She sued under the ADA, claiming associational disability discrimination.

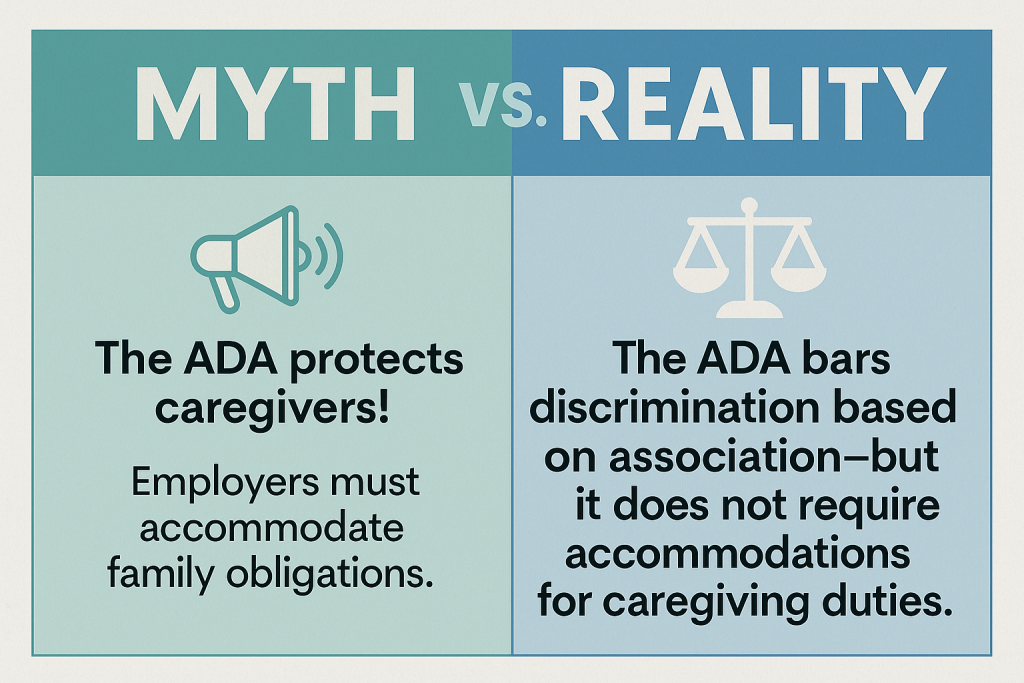

What the ADA actually protects—and what it doesn’t

The Americans with Disabilities Act prohibits employers from discriminating because of the known disability of an individual with whom the employee is known to have a relationship or association. That could be a spouse, child, or even roommate.

But this rarely-litigated provision of the ADA does not require employers to accommodate employees based on someone else’s disability. In other words, you can’t fire someone because their spouse is sick—but you also don’t have to grant them schedule changes or light duty to help with caregiving.

The Sixth Circuit’s decision in Stansberry v. Air Wisconsin outlines three primary ways associational bias can arise under the ADA:

- Expense-based bias: When the employer fears the employee’s family member will generate costly health care claims under the company’s insurance plan.

- Disability-by-association: When the employer fears the employee might contract or share the relative’s condition (for example, the employee’s partner has HIV and the employer fears the employee may become infected), or when the employer believes the employee is genetically predisposed to develop a disability that runs in the family.

- Distraction-based bias: When the employer assumes the employee will be too distracted, unreliable, or absent due to caregiving responsibilities.

Although the Eleventh Circuit didn’t spell these out in the decision you’re reading about, the plaintiff’s claim fits squarely within that third “distraction” category.

Why the claim didn’t stick

The court emphasized that there must be evidence the decision was actually based on the known disability of the associated person. In this case:

- The employer had objective hiring data backing the decision.

- The supervisor’s “lay off of” comment—allegedly tied to her husband’s illness—was vague and not connected to the promotion decision.

- The plaintiff offered no evidence that the comment was made to anyone on the promotion panel—or that the panel even knew about her husband’s illness.

Without that causal link, the ADA claim failed.

3 Takeaways for Employers

✅ Objective criteria are your best defense. Use structured interviews, matrices, and documented scoring to explain promotion decisions.

✅ Train managers to avoid speculation. Remarks about an employee’s personal life—even vague ones—can open the door to litigation.

✅ Understand the ADA’s limits. The ADA bars discrimination based on someone else’s disability—but it does not require accommodations for caregiving obligations.

🔹 Your mileage may vary under state law—and certainly under the FMLA, which requires covered employers to provide leave to eligible employees to care for a spouse with a serious health condition.

Bottom line:

The ADA prohibits treating employees worse because of a family member’s disability—but it doesn’t protect against neutral decisions, even if they impact a caregiver. Employers can (and should) be empathetic—but they aren’t legally required to offer accommodations based on association alone.

The Employer Handbook Blog

The Employer Handbook Blog