Search

When policy violations aren’t hacking: Third Circuit shuts down employer’s scorched-earth lawsuit

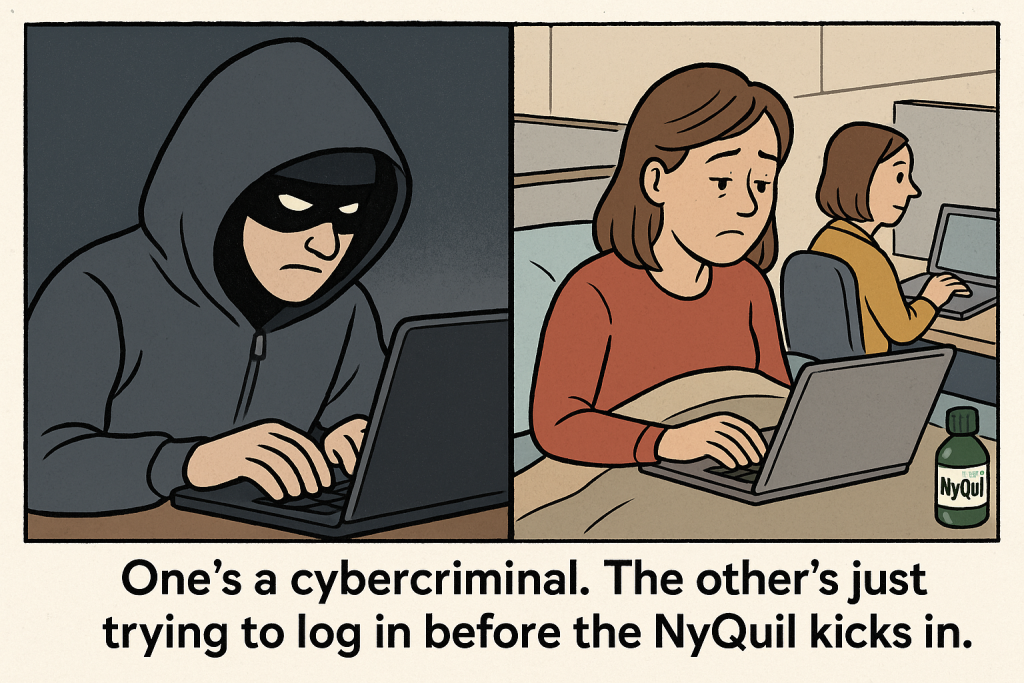

It started with a sick day, a spreadsheet literally called “My Passwords.xlsx,” and a colleague trying to help. It ended with a company accusing two former employees of federal computer crimes and trade secret theft.

The Third Circuit’s response? Nice try — but workplace policy violations aren’t hacking.

TL;DR: The Third Circuit affirmed dismissal of an employer’s claims that two former employees committed “computer fraud” and stole trade secrets when one emailed the other her own password spreadsheet while home sick. The court held that violating computer-use rules isn’t hacking, passwords themselves aren’t trade secrets, and employers risk overreach when they turn routine workplace violations into federal lawsuits.

The facts behind the fight

While home sick with COVID, one employee needed urgent access to a company system. She had no remote login but had created a file on her office computer called “My Passwords.xlsx.” With her permission, a colleague logged in under her credentials and emailed her the file.

The spreadsheet contained logins for internal systems but no customer data. Both employees had already complained about persistent harassment at work, and one alleged that an executive even slapped her. Within weeks of those complaints, one resigned and the other was fired. Soon after, the company sued them, claiming:

- computer fraud under the CFAA

- federal and state trade secrets violations

- civil conspiracy, fraud, and breach of loyalty

The employees countered with claims of harassment and retaliation.

Why the claims collapsed

When a federal appellate court kicks things off with “In the wrong hands, the law becomes a hammer in search of a nail. This is one such case,” you know you’re in trouble. That’s not judicial throat-clearing. That’s the opinion-writing equivalent of a judge rolling their eyes and saying, “Really? This is what you brought us?”

The employer had tried to turn everyday rule-breaking into federal crimes. It leaned on the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, a statute written in the 1980s to stop hackers from breaking into government and business systems. But the women here weren’t hackers. They were employees with valid access. One shared her credentials with a colleague, and a password spreadsheet was emailed. That might be a policy violation, but it isn’t “unauthorized access” under the CFAA. The court stressed that “a mere violation of a workplace computer-use policy should not create a claim under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), as doing so would attach criminal penalties to a breathtaking amount of commonplace computer activity.” Put simply, the statute doesn’t transform workplace slip-ups into federal offenses.

The trade secrets claims collapsed just as quickly. The company argued that the passwords themselves were proprietary business information. The Third Circuit disagreed. Passwords may protect trade secrets like customer lists or pricing data, but the logins themselves aren’t intellectual property. They don’t have independent economic value. So, calling them trade secrets would stretch the law far beyond what it was designed to do.

That left the state-law theories: conspiracy, breach of loyalty, fraud. The civil conspiracy claim was unsuccessful because there was no clear objective behind the conspiracy and the employees acted without malice. The employees did not breach their common-law duty of loyalty since they did not compete against their employer. Additionally, the employee did not commit fraud by collecting bonuses on accounts she genuinely believed were eligible for bonus payments, even if her belief turned out to be incorrect.

Employer takeaways

✔ Few rule infractions are federal cases. Firing or reprimanding an employee for password sharing is fair game, but don’t assume it’s a federal crime.

✔ Protect real trade secrets. Customer lists, pricing formulas, or algorithms qualify — passwords do not.

✔ Mind retaliation optics. Suing former employees right after they complain of harassment can look retaliatory and may give traction to an otherwise weak discrimination or harassment claim.

✔ Tighten technology controls. If password sharing is a risk, fix it with access controls and training instead of relying on lawsuits later.

The bottom line

The CFAA was built to stop hackers, not employees breaking IT rules. Employers who confuse the two risk costly defeats and accusations that they are weaponizing the law against whistleblowers.

The Employer Handbook Blog

The Employer Handbook Blog