Search

When Is a “Religious Belief” Actually Religious? A New Federal Case Helps Employers Draw the Line

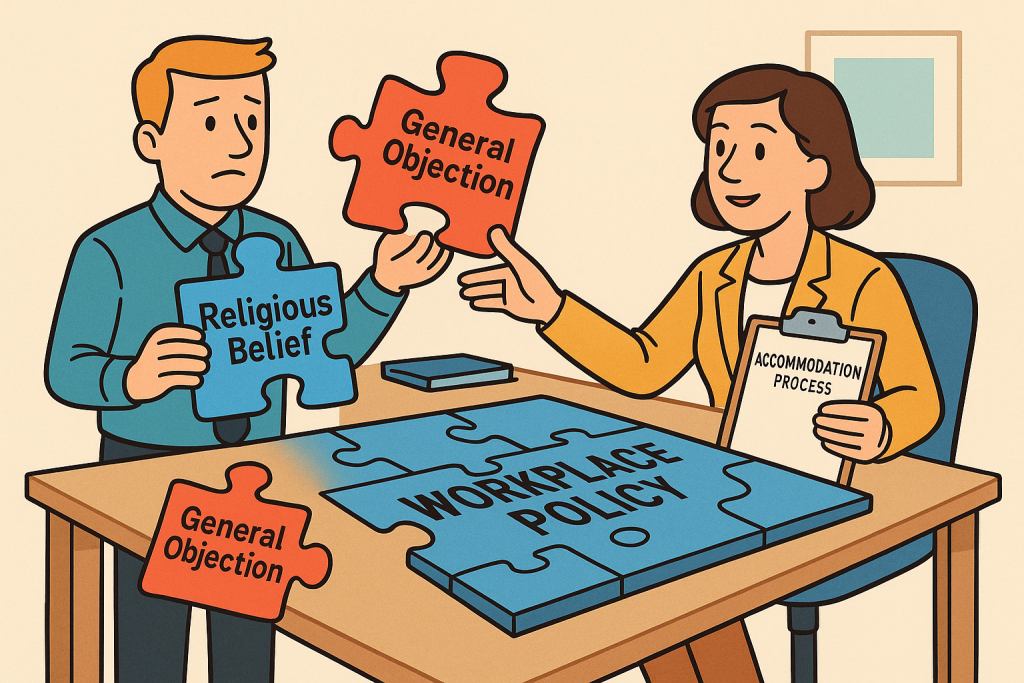

Some accommodation requests are straightforward. Others arrive wrapped in spiritual language but turn out to be personal views, broad objections, or political frustrations. A recent federal decision breaks down the elements courts look for in separating religious beliefs from non-religious objections.

TL;DR: A federal court just explained how to separate genuine religious beliefs from personal or political objections under the full name of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The employee described a religious conflict with the COVID-19 vaccination requirement, which the court treated as rooted in a faith-based practice. But his broad objection to the testing requirement was too political and too sweeping to qualify as religious.

The Policy, The Objection, And The Road to Litigation

The employee in this case had worked fully remotely for years, aside from occasional in-person meetings. In late 2021, his employer adopted a policy requiring all employees to receive a COVID-19 vaccination as a condition of employment. Remote employees were included. The policy allowed employees to request religious exemptions, and the employee sought one.

In support of his request, he explained that he is an evangelical Christian who believes his body is a temple, that he avoids modern medical intervention, and that neither he nor his family receive any vaccines. He also submitted a letter from his pastor. The employer granted the exemption.

At that time, employees who received a religious exemption were not required to undergo diagnostic testing if they worked remotely. That changed in early 2022, when the employer extended its testing requirement to fully remote workers who had received COVID-19 vaccination exemptions.

The employee sought another accommodation. This time, instead of relying on his previously described religious practice, he objected more broadly, stating that God had instructed him to avoid the “covid agenda” entirely. The employer denied that second request. A month-long back and forth followed, during which the employee refused to comply with the testing requirement. The employer ultimately terminated his employment, and he sued.

The remaining question was whether his objections to each requirement were religious in nature or instead reflected political, philosophical, or personal views.

How Courts Separate Religious Beliefs From Everything Else

Before turning to each requirement, the court emphasized a foundational principle. Determining whether a belief is religious is a careful, fact-sensitive task. Courts do not evaluate the truth or plausibility of anyone’s beliefs. They do, however, assess whether an objection is actually rooted in religion or instead reflects political, philosophical, or personal views. Religious language alone does not transform a secular objection into a religious one. Title VII also does not give employees a blanket privilege to create their own standards whenever a workplace rule conflicts with their preferences.

Against that backdrop, the court evaluated each objection separately.

The Testing Requirement: A Political Objection, Not a Religious One

When the employer extended its testing requirement to remote workers, the employee’s new accommodation request shifted in tone. Rather than pointing to his faith-based aversion to medical intervention, he asserted that, after prayer and fasting, God directed him to avoid the “covid agenda” and not “com[e] into agreement with any aspect of it.”

The court concluded that this objection did not qualify as religious. It was:

- sweeping and undefined

- not tied to a faith-based practice

- framed in terms of political and moral disagreement

- open-ended in a way that would allow the employee to reject any requirement he associated with that agenda

As the court explained, “Courts have not accepted the proposition that Title VII protects what a plaintiff essentially asserts is a divinely granted right to pick and choose.”

Because the objection was not religious in nature, the testing-policy claims did not move forward.

The COVID-19 Vaccination Requirement: A Faith-Based Conflict

The employee’s objection to the COVID-19 vaccination requirement rested on a different foundation. He alleged that:

- he is an evangelical Christian

- he believes his body is a temple

- he avoids modern medical intervention

- he relies on prayer and natural remedies when God directs him

- he and his family receive no vaccines

- his pastor supported this belief in writing

These allegations described a specific faith-based approach to medical treatment. The employee tied his objection to a religious practice he says he follows consistently. The court accepted that this objection reflected a religious conflict with the vaccination requirement.

As a result, the vaccination-related claims proceeded.

Four Practical Lessons For Employers Reviewing Religious Accommodation Requests

Although this decision spent most of its time on whether each objection was religious in nature, employers should remember that their real-world focus should be on the accommodation process. Courts expect employers to avoid acting like theologians and to move into problem-solving once they are on notice of a conflict.

1. Start from the presumption that the belief is religious and sincerely held, unless you have objective evidence to question it.

Employers may ask clarifying questions, but they cannot evaluate whether a belief is correct, logical, or theologically sound. Only clear, tangible inconsistencies or evidence of non-religious motives justify probing sincerity.

2. Focus on the conflict between the employee’s belief and the specific requirement.

The key question is how the employee’s stated practice conflicts with the policy. As this case shows, different parts of the same policy may raise different issues.

3. Shift quickly into the accommodation discussion.

Once an employer understands the claimed conflict, the next step is exploring reasonable options. Courts expect employers to evaluate whether accommodation is possible before defaulting to denial.

4. Document the dialogue and your reasoning.

A well-documented process — what you asked, what the employee said, what options you considered, and why you landed where you did — carries far more weight than debating religious doctrine.

The Bottom Line

Courts are willing to draw the line between personal or political objections and actual religious conflicts. When a workplace requirement genuinely conflicts with an employee’s religious practice, employers must engage in the accommodation process. When an objection is broad, political, or untethered from any religious principle, it is far less likely to qualify for protection.

The Employer Handbook Blog

The Employer Handbook Blog