Search

The Low Bar for Whistleblower Claims in New Jersey

Whistleblower cases do not begin with evidence and proof. They begin with allegations. If those allegations are plausible, employers get forced into discovery. Under CEPA, that bar is very low.

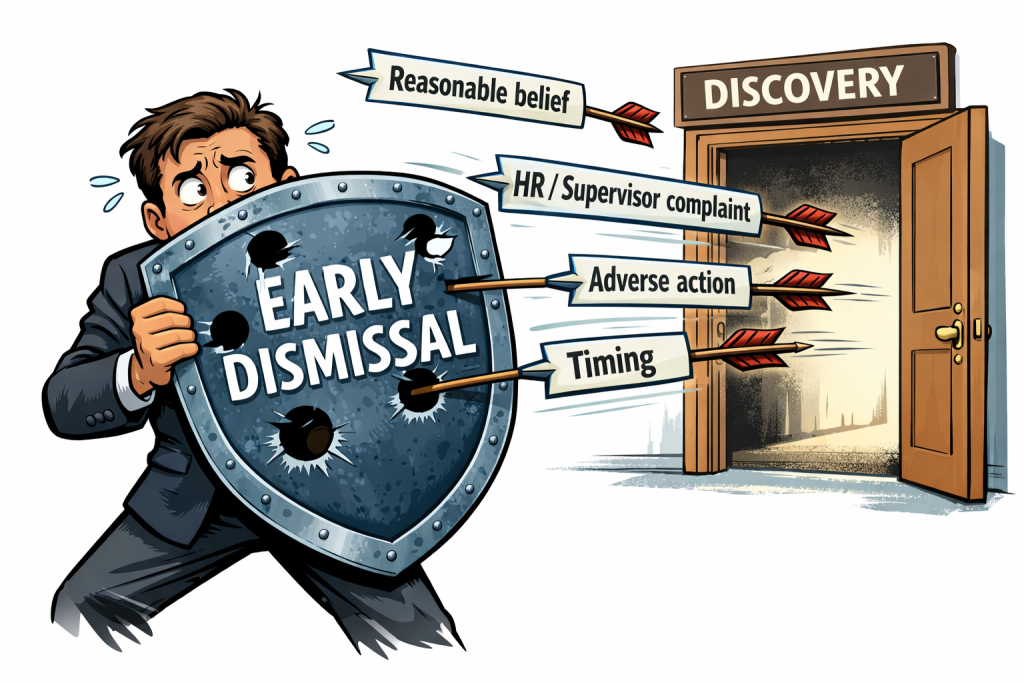

TL;DR: At the motion-to-dismiss stage, a claim under the New Jersey Conscientious Employee Protection Act (CEPA) does not require proof that any law was actually violated. It requires factual allegations supporting a reasonable belief that the employer’s conduct was unlawful. Internal reporting to HR or to a supervisor, an adverse employment action, and close timing are usually enough to make retaliation plausible and push the case into discovery.

The timeline that doomed the motion to dismiss

From a defense perspective, none of this is exotic. This is exactly how ordinary HR issues turn into CEPA cases.

According to the complaint, the employee alleged:

-

She believed company leadership was using proprietary materials from a former employer in violation of trade secret and intellectual property laws.

-

She spoke with HR on May 14, 2024, and filed a formal HR report on May 17, 2024.

-

HR allegedly delayed submitting the report and later told her it had been filed “anonymously,” despite an understanding that it would be filed in her name.

-

On June 26, 2024, she allegedly received a negative performance review and was told her role would be eliminated and that there was “no place” for her at the company.

-

Later, she alleged her annual bonus was cut by fifty percent and she was given notice that her employment would end.

That is the factual sequence the court accepted as true for purposes of the motion.

This case was not decided on the merits. It was allowed to proceed. The ruling answered only a procedural question: whether the complaint contained enough factual allegations to make retaliation plausible under CEPA.

Why this case survived: CEPA’s pleading standard is employer-unfriendly

This was a motion to dismiss, not a motion for summary judgment. The court was not deciding who was right or whether any law was actually broken. It was deciding a narrower question: do the allegations, taken as true, make retaliation plausible under CEPA?

At this stage, the court does not weigh evidence, assess credibility, or choose between competing explanations. It assumes the employee’s version of events is true and asks only whether those facts, on their face, could support a whistleblower retaliation claim.

CEPA does not require proof of an actual legal violation at the pleading stage. It requires allegations supporting a reasonable belief that the employer’s conduct violated the law. That belief must be objectively plausible, even if it ultimately proves to be mistaken. An employee does not have to be correct about whether misconduct occurred. She has to plausibly allege facts showing that her belief was reasonable.

That is why the employer’s argument that no trade secret violation really occurred missed the point. Correctness is tested later. Plausibility is the only question now.

CEPA also does not require outside reporting. This case did not involve regulators, subpoenas, or government agencies. It involved HR. Once an employee raises suspected illegality internally, CEPA protection is triggered. For many employers, that is the moment whistleblower risk actually begins.

Then timing did the final piece of work.

A report in mid-May.

A negative review and job-elimination message in late June.

That proximity alone was enough to plausibly allege causation, even though the termination itself came months later. Courts routinely allow causation to be inferred from close timing at the motion-to-dismiss stage, particularly in CEPA cases, which are construed liberally in employees’ favor.

Employer takeaways

-

If you see these four things together, there is CEPA litigation risk: alleged illegality, an HR or supervisor complaint, any negative employment action, and tight timing. That combination is usually enough to reach discovery.

-

CEPA is built on reasonable belief, not proof of an actual violation, from pleading through trial.

-

Internal complaints trigger whistleblower protection. You do not need regulators or outside agencies. Once an employee reports concerns to HR or to a supervisor, CEPA is in play.

-

Lock in business decisions before complaints arrive. If a reorganization, role elimination, or performance action is already planned, your documentation and timing must exist before a whistleblower report is filed.

-

An investigation clearing the complained-of conduct does not end the CEPA analysis where a nexus may exist between the report and a subsequent adverse action.

Bottom line

This case was not won. It was allowed to proceed.

And under CEPA, that is often the real fight.

The Employer Handbook Blog

The Employer Handbook Blog