Search

Sometimes the case ends because the plaintiff says the quiet part out loud

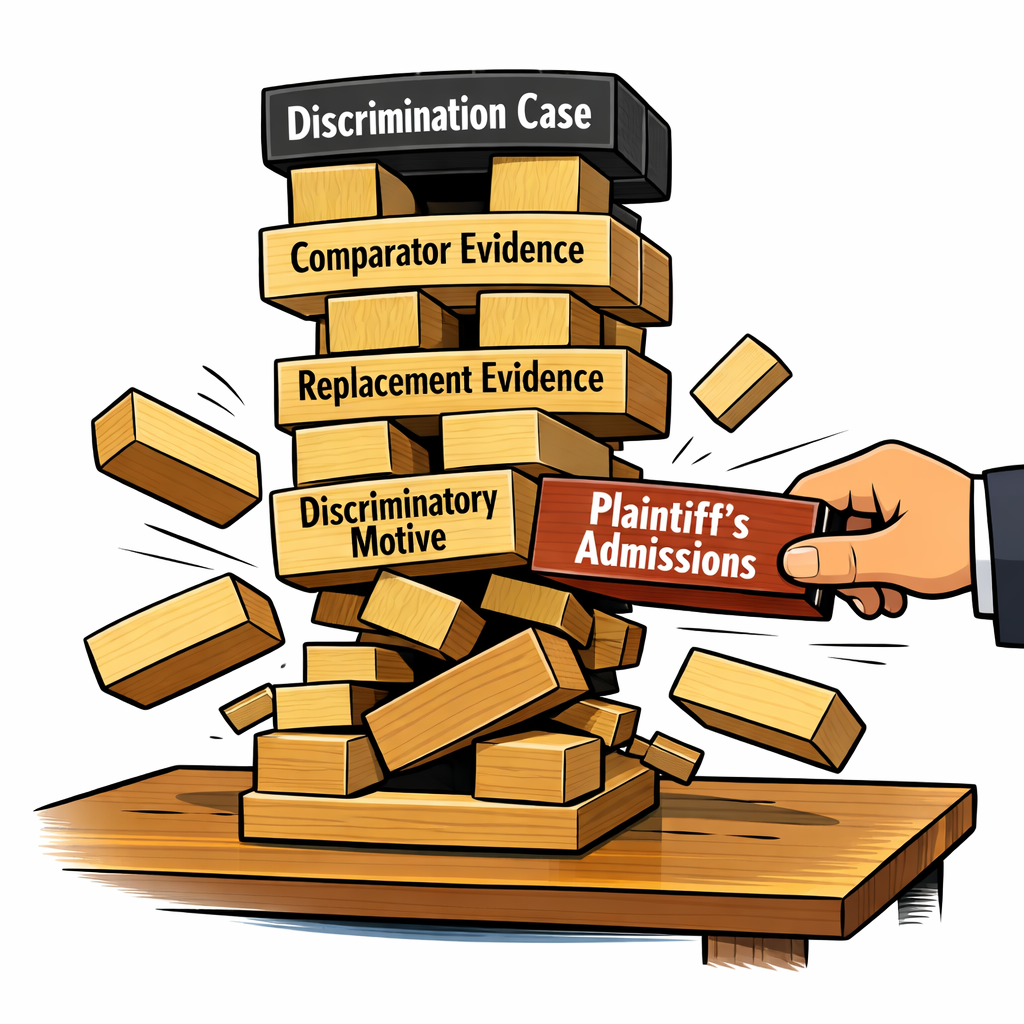

Most employment cases fall apart because the evidence is thin or the comparators don’t line up.

This one fell apart because of what the employee herself admitted – under oath.

TL;DR: A Sixth Circuit panel affirmed summary judgment for an urgent care clinic after a front-desk employee was terminated following inappropriate comments to a police officer seeking treatment. The employee’s own deposition testimony defeated her hostile work environment claims, while her discrimination claims failed for lack of replacement or comparator evidence. Without proof tying the decision to race or gender, the case never got off the ground.

A front-desk job where professionalism is the job

The employee worked as a patient service specialist at the front desk of an urgent care clinic. During a shift, a uniformed police officer came in for treatment. While a coworker handled registration, the employee engaged the officer in what she later described as “small talk,” including asking whether he had ever killed anyone.

The officer complained to his supervisor, who arrived at the clinic shortly thereafter. According to the supervisor, the employee made additional inappropriate remarks. The employee disputed that account.

After the encounter, the employee texted the clinic manager, referring to the supervisor as a “grumpy old man” and asking to leave early because she was concerned about him running her expired vehicle tags.

The clinic suspended her that day pending investigation. The following morning, the police chief contacted management, expressed that the department was upset, and said it would likely sever its relationship with the clinic. Later that day, management and HR terminated the employee for her conduct.

The discrimination claims stalled at the starting line

The employee sued, alleging race and gender discrimination and a hostile work environment under federal and state law. The district court granted summary judgment for the employer, and the Sixth Circuit affirmed.

On the discrimination claims, the problem was fatal from the outset. The employee admitted she did not know who replaced her or whether she was replaced at all. And her proposed comparators were little more than speculation – unnamed employees, unknown conduct, and unknown outcomes.

As the court put it, “conclusory allegations, speculation, and unsubstantiated assertions are not evidence,” and they are not enough to survive summary judgment.

That ended the disparate treatment claims before the court ever reached pretext.

The admissions that quietly ended the harassment claims

The employee’s own testimony ended the harassment claims.

Asked whether she believed the employer harassed her because of her race, she answered:

“[N]o, I don’t believe that they harassed me because of my race. I believe they harassed me because of what the police officer said.”

She also disclaimed any gender-based motive, testifying that her termination was “not from [the employer], no,” and confirmed that she never complained internally about harassment.

That was enough. As the Sixth Circuit put it, because the employee herself did not believe the conduct was based on race or gender, “no reasonable jury could find that [the employer] subjected her to a hostile work environment.”

With those admissions in the record, the court had no reason to analyze severity, pervasiveness, or workplace context. The claims failed on the employee’s own words.

Why moving fast didn’t create liability

The employee argued that the clinic acted too quickly and out of reputational concern. The court did not dispute that the employer moved fast.

But Title VII does not prohibit employers from responding promptly to serious complaints or protecting business relationships. What matters is whether the decision is tied to a protected characteristic. Here, it wasn’t.

What employers should take away

- Roles that interact directly with the public deserve extra attention. Expectations are higher, and the margin for error is smaller.

- Be explicit about professionalism in public-facing roles. Employees should not be left guessing where casual conversation ends and workplace standards begin.

- Intent may explain behavior, but impact is what drives employment decisions. Focus on how the conduct was received, not how it was intended.

- Act promptly, but with structure. Move quickly when needed, but ground decisions in a clear, repeatable process.

- Apply standards consistently. Similar conduct should lead to similar outcomes, independent of personalities or context.

The bottom line

This case did not fail because the employer ran a flawless investigation. It failed because the record – including the employee’s own testimony – never tied the outcome to race or gender.

Sometimes, the most important evidence isn’t what the employer says or does.

It’s what the plaintiff admits.

The Employer Handbook Blog

The Employer Handbook Blog