Search

Remote Work as an Accommodation Still Comes With Performance Expectations

When an employee’s health takes a turn, the instinct is to be flexible. The legal risk is assuming flexibility means you cannot enforce expectations.

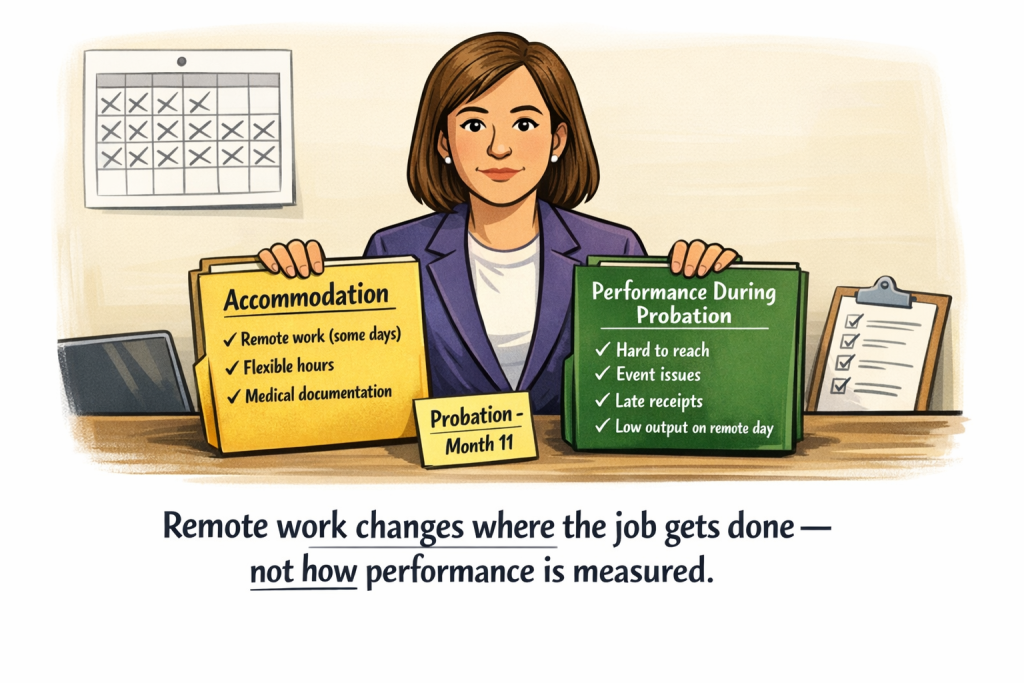

TL;DR: The Eleventh Circuit affirmed summary judgment for a county employer that ended a probationary employee’s employment after documenting performance problems, even though the employee had serious medical conditions and was allowed to work from home on some days with flexible hours. The court held the employee did not present direct evidence of disability discrimination and could not show the employer’s performance-based explanation was pretext under either McDonnell Douglas or a “convincing mosaic” theory.

📄 Read the Eleventh Circuit’s opinion

Quick correction from yesterday’s NJFLA post:

I said NJFLA coverage would drop from 15 employees to 10 and then to 5. That is not what the final law says. The statute goes from 30 employees to 15 employees, and it stops there.

For the record, I know what bracketed language means in a bill. It’s basically a legislative strikethrough. I didn’t misunderstand it. I just… didn’t see it. Apparently, my eyes skimmed right past the part that said “this text did not make the final version.”

That one’s on me. Thanks to the sharp-eyed readers who caught it before I accidentally scared every 9-employee employer in New Jersey into a full-on compliance panic.

The probationary job, the health crisis, and the accommodation

A county animal services department hired an employee as an outreach specialist responsible for booking and hosting pet adoption events. The position required successful completion of a 12-month probationary period before the employee could attain civil service status.

Several months into probation, the employee developed serious health issues and was diagnosed with a brain tumor, thyroid masses, and an autoimmune disease. After she provided medical documentation, the employer allowed her to work from home on some days and to work flexible hours, provided she still worked eight hours each day.

The accommodation did not sit well with everyone. According to the employee, a department leader questioned how long the work-from-home arrangement would continue and whether it could end sooner.

The performance record that followed

After the employee began working remotely at times, her relationship with coworkers deteriorated. She said colleagues were less responsive and less willing to help with events. She also claimed she overheard a supervisor suggest she was “faking it” and that there was no way she had a brain tumor.

At the same time, supervisors documented a series of performance concerns during the probationary period. The record included recurring complaints about communication, event-planning problems, and a finance-division complaint about receipts from an event not being timely submitted. The employee did not dispute that the receipts were overdue, though she denied responsibility for submitting them. Management also cited inefficiency while working from home, including a specific day on which the employee allegedly produced little work output while reporting four hours of time.

Eleven months into the probationary period, the supervisor notified human resources that she intended to conclude the employee had failed probation. Human resources prepared a failure-of-probation letter, which a department leader signed. At a subsequent meeting, an HR leader explained to the employee that the decision was not about her health issues, but about performance and her inability to give “100%” right now.

The employer contended the employee resigned. The employee contended she was terminated. For purposes of the appeal, the court assumed she was terminated.

Why the county won

The employee sued under the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Florida Civil Rights Act, alleging her employment ended because of her disability.

The Eleventh Circuit affirmed summary judgment for the employer.

First, the court held the employee did not present direct evidence of disability discrimination. The statements made during the probation-failure meeting were ambiguous and open to interpretation, not the kind of blunt remark that proves discriminatory intent without inference.

Second, the employee could not show pretext. The court focused on the employer’s stated reasons—complaints about lack of communication and the employee’s admitted failure to timely submit receipts—and concluded the employee had not shown those reasons were false. The court also reiterated a familiar principle: it does not decide whether an employer’s reasons were prudent or fair. The only question is whether discrimination was the real reason.

The employee also tried to survive summary judgment under a “convincing mosaic” theory. That effort failed as well. Taken as a whole, the evidence showed workplace frustration with remote work and a belief that performance suffered, not intentional disability discrimination by the decisionmaker.

Three employer takeaways

If remote work is the accommodation, keep expectations concrete.

Spell out deliverables, responsiveness requirements, and coverage expectations. Flexibility works best when expectations are clear.

Document performance issues while the accommodation is in place.

This case turned on the employee’s inability to show the employer’s reasons were false. Contemporaneous, specific documentation mattered.

Train supervisors to stay out of the medical lane.

Comments like “she’s faking it” are litigation kindling. Supervisors should focus on observable performance and expectations, not medical speculation.

Bottom line

Accommodation and accountability can coexist. A probationary period still means something, and courts will not second-guess an employer’s honestly held, performance-based decision when the record supports it.

The Employer Handbook Blog

The Employer Handbook Blog