Search

Hostile Work Environment Claims After Muldrow: What Changed, What Didn’t, and Why Courts Are Drawing the Line

Several readers of this blog have floated the idea that Muldrow v. City of St. Louis — the Supreme Court’s recalibration of what counts as actionable harm in discrimination cases — might ripple into harassment standards. One federal appellate court recently explained why it doesn’t.

TL;DR: The Tenth Circuit held that Muldrow v. City of St. Louis is a discrete-act decision and declined to extend it to hostile work environment claims. Harassment claims still require conduct that is sufficiently severe or pervasive to alter the conditions of employment.

📄Read the Tenth Circuit opinion

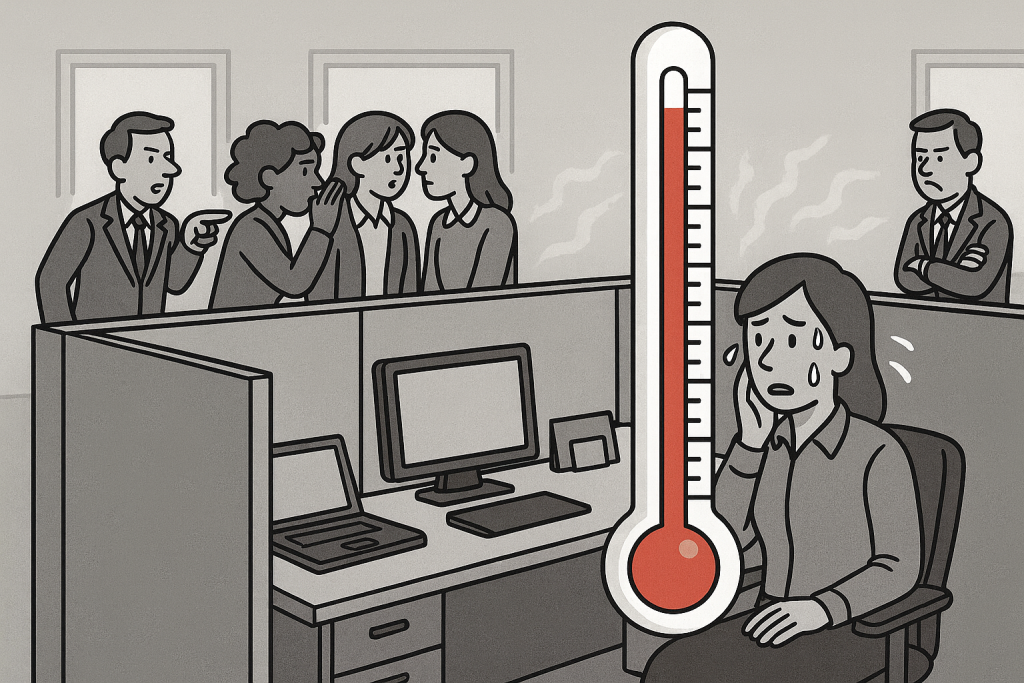

The Run-Up to a Hostile Environment Claim

A civilian Army employee claimed his new supervisor subjected him to a gender-based hostile work environment. According to him, she held gender-segregated meetings, treated men and women differently in access and assignments, and repeatedly singled him out by criticizing prior decisions, altering his email signature, removing him from a leadership distribution list, and copying others on an email about a personal financial matter that he viewed as embarrassing.

An internal investigation later found that her conduct reflected gender bias but did not assess whether it was severe or pervasive. The plaintiff sued under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VII), and the district court granted summary judgment because the alleged behavior did not meet the hostile environment standard. He appealed.

Why the Severe or Pervasive Standard Survived Muldrow

The Tenth Circuit’s opinion is noteworthy for how directly it confronts the question many practitioners have quietly posed since Muldrow: does lowering the injury threshold for certain discrimination claims necessarily spill into harassment law? The court explained why the answer is no, and why the severe or pervasive standard remains intact.

1. Discrete acts and hostile environments are fundamentally different

The court began with first principles. Title VII claims fall into two categories:

Discrete acts

These involve one-time decisions such as firings, denials of promotion, or reassignments. Muldrow addressed the level of harm required for these claims, lowering the threshold for what counts as actionable injury.

Hostile environments

These often cover situations where workplace conduct adds up, bit by bit, to the point that it changes someone’s working conditions. The Supreme Court has outlined this standard in cases like:

- Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson

- Harris v. Forklift Systems, Inc.

- Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services, Inc.

Because the two theories serve different purposes, the Tenth Circuit declined to extend Muldrow beyond the discrete-act context addressed by the Supreme Court.

2. The Supreme Court has already defined harassment, and Muldrow never touched that standard

The severe or pervasive test is not something lower courts invented. It comes directly from Supreme Court precedent.

In Harris, the Court held that a hostile environment exists when the workplace is permeated with discriminatory intimidation, ridicule, and insult that is sufficiently severe or pervasive to alter the conditions of employment.

Muldrow did not discuss harassment. It did not mention severe or pervasive. It did not cite or question Meritor, Harris, or Oncale.

The Tenth Circuit relied on Rodriguez de Quijas v. Shearson/American Express Inc., where the Supreme Court instructed lower courts to apply the decision that directly governs unless the Supreme Court itself overrules it.

3. Removing the severe or pervasive test would erase the concept of a hostile environment

The Tenth Circuit emphasized that without a severity or pervasiveness requirement, hostile environment claims would collapse into discrete-act claims.

Hostile environment doctrine exists precisely because much workplace misconduct is not actionable in isolation. It becomes unlawful only when it crosses the severe or pervasive threshold.

Eliminating that threshold would turn Title VII into the general civility code the Supreme Court warned against in Oncale.

Muldrow did not signal any intent to rewrite that boundary.

4. Other circuits are rejecting attempts to apply Muldrow to harassment

The Tenth Circuit noted that:

- The Fourth Circuit reached essentially the same conclusion in Hansley v. DeJoy.

- The Fifth Circuit likewise declined to apply Muldrow to hostile environment claims in Dike v. Columbia Hospital Corp. of Bay Area.

- The Sixth Circuit took a broader view in McNeal v. City of Blue Ash, but the Tenth Circuit found its reasoning circular and unpersuasive.

These decisions show a growing trend of courts declining to extend Muldrow to harassment claims, though the Sixth Circuit’s broader reading in McNeal signals that this issue is now developing into a circuit split rather than a settled consensus.

Why the Plaintiff Still Lost Under the Traditional Standard

With the legal standard reaffirmed, the outcome was predictable. Even accepting the plaintiff’s evidence, the conduct did not rise to the level required to alter the conditions of employment.

The internal investigation did not analyze severity or pervasiveness, and the district court correctly declined to rely on its conclusions. The Tenth Circuit noted the plaintiff had waived any argument about the report’s legal effect.

The alleged conduct described friction, uneven treatment, and unprofessional behavior. Title VII requires more before labeling a workplace hostile.

What Employers Should Take from this Decision

1. Harassment law remains unchanged after Muldrow

The severe or pervasive standard is fully intact.

2. Courts will not apply Muldrow beyond discrete discrimination claims

The Tenth Circuit’s analysis provides a model for courts nationwide.

3. Employers should still respond promptly to bias concerns

Even biased conduct that falls short of harassment warrants attention and investigation.

The Bottom Line

Muldrow reshaped certain discrimination claims, but hostile environment law remains exactly where the Supreme Court left it. The severe or pervasive standard is alive and well, and courts are not relaxing it anytime soon.

The Employer Handbook Blog

The Employer Handbook Blog