Search

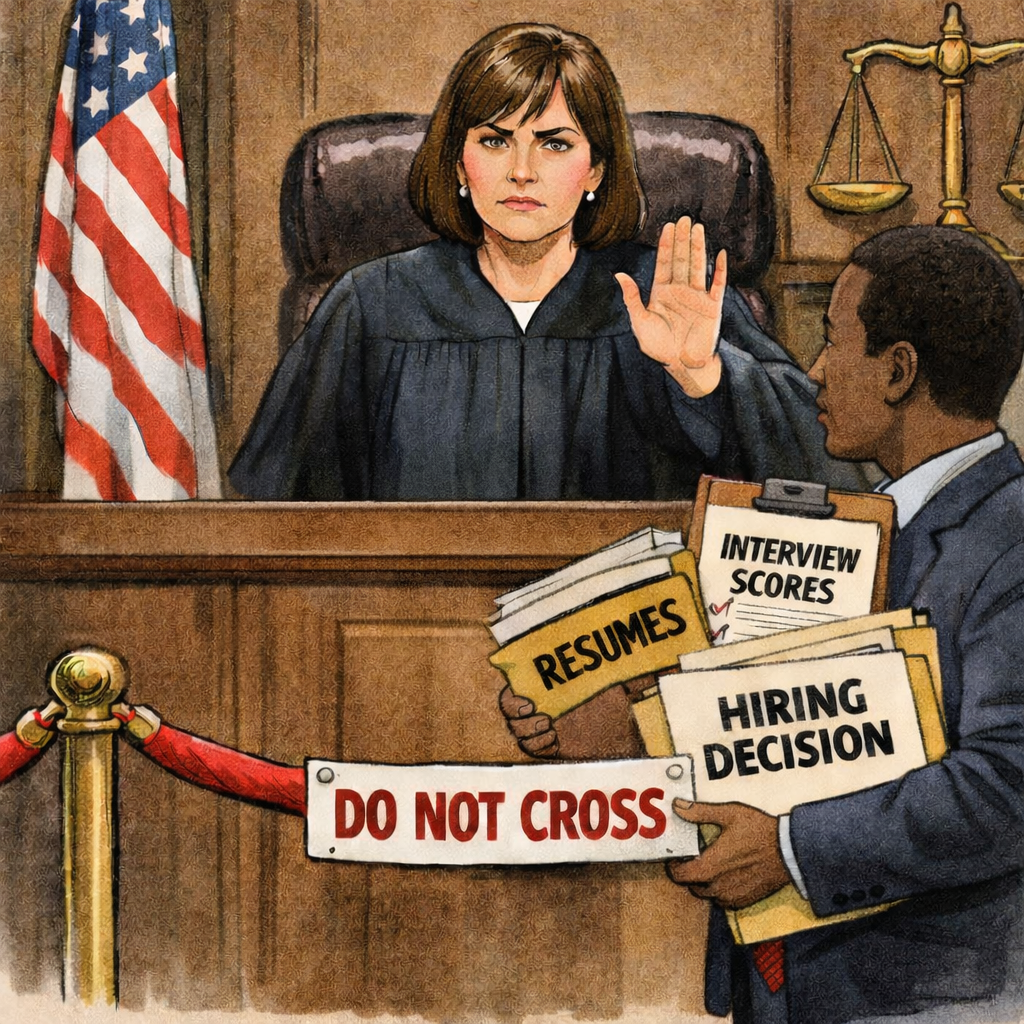

Courts Are Not Super-Personnel Departments (And This Promotion Case Proves It)

Courts see plenty of promotion disputes that boil down to one familiar complaint: I should have gotten the job.

The Fourth Circuit just explained why that argument usually is not enough.

TL;DR: In a published decision, the Fourth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for an employer facing a Title VII failure-to-promote claim. Even assuming the employee could establish a prima facie case, she could not show pretext where the employer selected another candidate based on job-related criteria, interview scoring, and management experience. Courts do not act as “super-personnel departments” second-guessing promotion decisions.

Courts Don’t Re-Run Promotion Decisions

The employee applied for a senior leadership role at a community college. A search committee interviewed candidates using standardized questions, scored their responses, and recommended one candidate. A vice president made the final decision and accepted that recommendation.

The employee sued, alleging race- and gender-based discrimination under Title VII.

The Fourth Circuit ruled for the employer and made one thing clear. Even giving the employee the benefit of the doubt, the case still failed.

Why? Because the court refused to second-guess the employer’s promotion decision. Judges do not decide who should have gotten the job.

“More Qualified” Is Not Enough

The employer’s explanation was straightforward. It selected the candidate it believed was more qualified for the role based on criteria it identified in advance, including experience managing large programs and budgets, familiarity with workforce-development systems, knowledge of WIOA funding, and grant-writing experience.

The employee countered with coworker opinions, testimony questioning the selectee’s leadership style, and her own account of her performance and program growth.

That did not create a jury issue.

The court emphasized that it is the perception of the decisionmaker that matters, not coworkers’ views or an employee’s self-assessment. Disagreement over qualifications, even sincere disagreement, does not establish discrimination. Absent evidence that the employee’s qualifications were demonstrably superior, the court would not intervene.

That is the core of the “super-personnel department” principle. Title VII does not authorize courts to re-grade interviews or substitute their judgment for an employer’s.

Preselection Still Isn’t Discrimination

The employee also argued the process was engineered to promote specific candidates.

The Fourth Circuit rejected that theory as well. Even if preselection occurred, the court explained, it disadvantages all applicants, black and white alike. Without evidence tying preselection to race or gender, it does not show discriminatory intent.

A flawed process is not the same thing as an unlawful one.

Stray Remarks Need a Real Nexus

The employee pointed to various comments by a supervisor as evidence of discriminatory animus. The problem was connection.

The supervisor was not the final decisionmaker, and the remarks were not tied to the promotion decision itself. The court reiterated that stray or isolated comments, especially those untethered to the challenged action, carry little weight in a failure-to-promote case. The lack of temporal proximity only weakened the inference further.

Later Discipline Didn’t Change the Analysis

The employee also relied on a later corrective action letter related to timecard approvals. That evidence did not move the needle.

The court noted that the discipline was divorced from the promotion decision and that the record reflected adherence to internal policy and HR guidance, not deviation or selective enforcement. Without evidence of similarly situated comparators or policy departures, the discipline did not suggest discriminatory animus.

What Employers Should Take Away

• 📋 Define and document promotion criteria. Courts measure qualifications against the employer’s standards, not the employee’s.

• 🎯 Use structured interviews thoughtfully. Scoring alone is not dispositive, but it supports a legitimate explanation when paired with job-related reasoning.

• 🧠 Train hiring managers on how to make and explain promotion decisions well. Clear criteria, thoughtful evaluation, and disciplined explanations lead to better hires and fewer second guesses later. Good hiring habits pay off long before anyone is thinking about a lawsuit.

• 🧭 Keep decision-making lines clear. Courts care who actually made the call and whether alleged bias is connected to that decision.

The Bottom Line

This decision is a textbook reminder that Title VII is not a vehicle for courts to referee promotion decisions.

When employers can point to job-related criteria, a structured process, and a coherent explanation for why one candidate was chosen over another, courts will not step in to play super-HR.

The Employer Handbook Blog

The Employer Handbook Blog