Search

When the EEOC Walks Away, Employees Can’t Sue the EEOC Instead

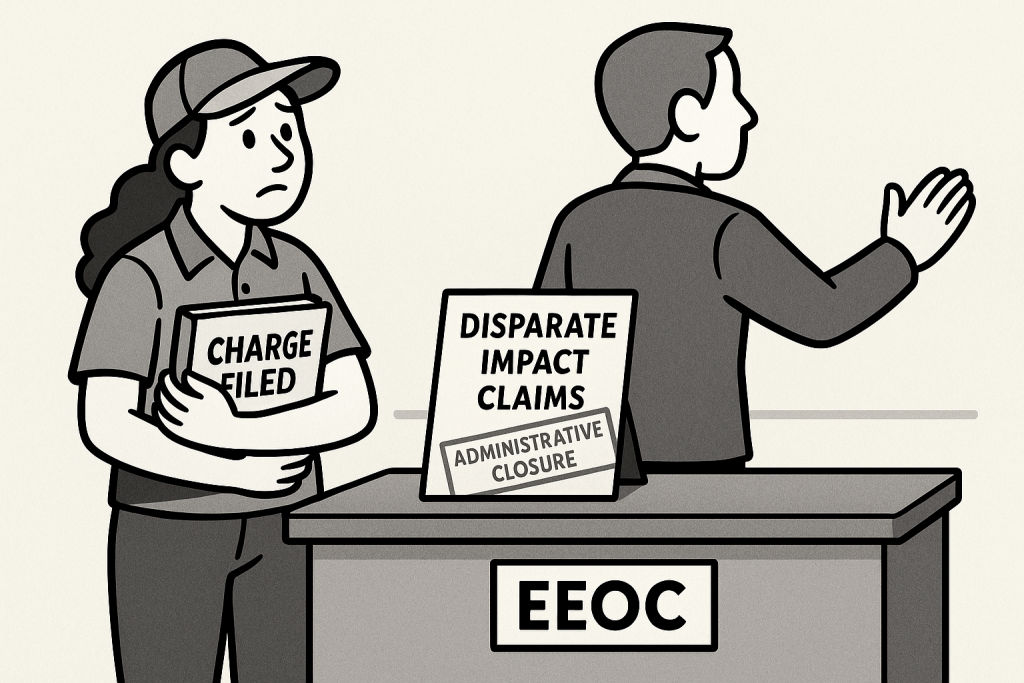

The EEOC’s decision to pull back from investigating disparate impact claims has been loud, controversial, and headline-worthy. And for employees watching their charges get administratively closed in real time, it can feel like the agency has simply walked away. But federal courts are not there to referee agency priorities or second-guess investigations.

TL;DR: A federal court dismissed an employee’s lawsuit against the EEOC after the agency administratively closed her disparate-impact charge following a shift in enforcement priorities. The court held that charging parties have no judicially cognizable right to a particular EEOC investigation, and no standing to force the agency to reopen one. Whatever the EEOC does or does not do, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 claims are litigated de novo against the employer – not the agency.

What Happened

The employee worked as an Amazon delivery driver and alleged that productivity quotas were so demanding that drivers could take bathroom breaks only by falling behind on deliveries. She claimed the policy had a disparate impact on women because male drivers could avoid restroom stops by urinating into bottles, while that workaround was not practical for women. She filed a charge with a state agency, which was later transferred to the EEOC.

The employee filed her charge with the Colorado Civil Rights Division in May 2023, and it was transferred to the EEOC’s Denver office in January 2024. The EEOC investigated for about two years and interviewed the employee in early 2025. In April 2025, President Trump issued an executive order directing agencies to deprioritize disparate-impact enforcement. In September 2025, the EEOC issued a memorandum requiring staff to close disparate-impact charges by the end of the month (while noting that investigators could still pursue disparate treatment theories if the facts supported it). The employee received a right-to-sue notice, and the EEOC administratively closed her charge.

Rather than suing her employer, the employee sued the EEOC. She claimed the agency violated the Administrative Procedure Act by ending its investigation early and by adopting its new enforcement policy without notice-and-comment rulemaking.

She asked the court to invalidate the EEOC’s internal memorandum, reopen her investigation, and toll filing deadlines for her and other charging parties whose cases were closed.

Why the Court Wasn’t Interested

The court never reached the merits. It dismissed the case at the threshold for lack of standing.

First, the court found no judicially cognizable injury. Longstanding precedent holds that private individuals have no enforceable right to dictate how the government investigates or prosecutes alleged violations by third parties. That principle applies equally to civil enforcement agencies. And although Title VII directs the EEOC to investigate charges, that language does not create an individual right to a particular scope, duration, or quality of investigation. Nor does it authorize courts to supervise how the agency allocates its limited enforcement resources.

Second, the court found no redressability. Ordering the EEOC to reopen the investigation would not guarantee a different outcome, and the court could not dictate how the agency conducted any renewed investigation. Vacating the EEOC’s internal guidance would not revive the employee’s closed charge, and prospective relief aimed at future cases would not remedy a past investigation.

Put simply, there was nothing the court could order that would actually fix the problem the employee complained about.

The Court’s Reminder About the Real Remedy

Title VII claims are litigated de novo. Courts do not defer to EEOC findings, non-findings, or investigative decisions. Whether the EEOC investigates aggressively, closes a charge quickly, or deprioritizes a category of cases altogether, the employee’s ability to sue the employer remains unchanged.

What Employers Should Take From This

- Enforcement priorities change – employer obligations do not. While the current EEOC has abandoned or deprioritized certain Biden-era guidance and enforcement theories, the underlying law has not changed. Disparate-impact liability remains part of Title VII, regardless of how aggressively the EEOC chooses to pursue it.

- State law and state agencies still matter. Even if a charge stalls or closes at the EEOC, employees may still have viable claims under state anti-discrimination laws, and state agencies may continue investigating or enforcing those claims independently. Employers should not assume that federal disengagement ends exposure at the state level.

- Courts remain the real battleground. Employers win or lose discrimination cases based on evidence, standards of proof, and credibility in court, not on how long an EEOC investigation lasted or why it ended.

The Bottom Line

If an employee is unhappy with the EEOC, that frustration does not create a lawsuit against the agency. This decision is a clean reaffirmation that federal courts will not supervise enforcement choices, and that employer exposure lives where it always has – in de novo litigation, not in the EEOC’s inbox.

The Employer Handbook Blog

The Employer Handbook Blog